Over the past decade, successive Australian governments have been in and out of hot water over climate policies. Having been a part of global climate agreements since the 1980s, Australia is not currently on track to meet goals set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The Climate Action Tracker currently labels Australia’s trajectory as insufficient to stop global warming below 2°C, let alone meet the Paris Agreement’s target of 1.5°C.

In 1997 when Australia first joined the Kyoto Protocol, they left as one of only three nations permitted to increase its emissions under the new deal. Since then, the nations’ tumultuous climate and energy saga has killed a number of prime ministers, including Malcolm Turnbull and Kevin Rudd, proving there is a strong national desire to establish regulations on carbon emissions.

Both the Coalition and Labor are currently making plans for solid climate policies for next year’s Federal Election, but internal conflicts have made the road there rocky. While policy is currently in the air, one thing is certain: the majority of Australians believe climate action needs to be taking place.

What is the stance of Labor?

Labor has long been divided when it comes to creating a solid climate policy. In February 2020, Opposition leader Anthony Albanese announced they were committed, if elected, to push for net zero emissions by 2050, and to oppose any future taxpayer support for new coal-fired power.

Internal debate within the Opposition around this time focused on the ‘risks of setting a concrete target in the absence of a roadmap to get there’, as well as the costs of these plans.

The majority in Labor favoured climate action and agreed with the target, but some believed that the Opposition’s eagerness for strong climate policy would cost them electorally.

In June 2020 in a speech to the National Press Club, Anthony Albanese committed Labor to creating a new medium-term emissions target ‘consistent with scientific advice’ before the next federal election. In the same breath, Albanese also announced an overture to Scott Morrison to ‘reach bipartisan agreement on energy policy’.

Looping back to the current day, Labor has still not settled on an appropriate mid-term target, and are in the midst of reshaping their climate policies due to a recent shadow cabinet reshuffle.

Cabinet Reshuffle

The longstanding clash over climate change policy led to Albanese announcing a cabinet reshuffle. On the eve of Federal Parliament’s return in January of this year, shadow minister Mark Butler was shifted from the climate portfolio, after having held it for the last eight years.

He will swap roles with former health spokesperson Chris Bowen, who has brought a focus on jobs to the climate portfolio, according to Albanese.

The current Labor policy of net-zero emissions by 2050 is staying put, but the spokesperson responsible has changed.

The reshuffle had been in sight since former minister and Hunter MP Joel Fitzgibbon resigned from the shadow cabinet in late 2020 over the Opposition’s net-zero emissions target.

The Otis Group

Last year an exclusive group nicknamed the Otis Group was formed. While most members of the Opposition did agree with the path Labor was taking, members of the Otis Group didn’t. This group aimed to push Labor toward a more ‘coal-friendly’ future, according to member Don Farrell.

Joel Fitzgibbon is an active member of the Otis Group — he had previously rallied for Labor to adopt the same weak 2050 target as the Morrison government in a bid to save the ‘political damage’ that Labor has created with their ‘ambitious climate policies’.

What is the stance of the Coalition?

The Coalition has also been long divided over climate change and energy policy, with no concrete commitment to a net-zero emissions reduction target by 2050.

The current emissions reduction target is 26%-28% below 2005 levels by 2030, which falls short of the requirements for the Paris Agreement. The Coalition had plans to meet this target using carryover credits from the Kyoto period, which has been strongly opposed by many nations.

In early 2020, Morrison announced that he would avoid signing up to an internationally imposed requirement of net zero emissions by 2050 by setting a technology investment target instead.

The debate within the Coalition over the 2050 target has been supported by moderate Liberal MPs. This is in complete contrast to the Nationals, led by Michael McCormack, who are passionately opposed to a net zero emissions target. McCormack even said he is “not worried about what might happen in 30 years’ time”.

Some Nationals MPs have spoken about exempting industries like agriculture and mining from the emissions, as to “not whack regional Australia in any way…just to get a target for climate in 2050”, as spoken by McCormack.

To the disappointment of the Nationals, the Morrison government seemed to change their position in early February this year.

‘Our goal is to reach net zero emissions as soon as possible, and preferably by 2050’.

Scott Morrison | National Press Club

While this isn’t yet a concrete target, it is a clear signal that Morrison wants to align the Coalition with the international standard of emissions reductions targets.

The Nationals will insist on a cost-plan and price assurance for farmers before agreeing to any target, which the ABC says may be confirmed before US President Joe Biden’s climate summit in April, which Morrison is set to attend.

Outside pressure starts to build

Despite the Nationals’ plan for agriculture to be exempt from the target, the National Farmers Federation (NFA) is in complete support of a net zero target for 2050.

In 2019, 10 groups representing businesses, farmers, unions, investors and environment advocates said that Australia should adopt a net zero policy pathway. Members include the Australian Industry Group, the Business Council of Australia, the ACTU and the Australian Council of Social Service, as well as the NFA.

It’s clear there is a lot of external pressure for the adoption of concrete plans, but we’re yet to see any solid progress.

Political commentators believe Morrison’s tone and choice of words on climate policy changed when Joe Biden was projected to become the next US president.

In the weeks leading up to the US election, politicians around the world reacted to Biden’s pledge to shift the US back into the Paris deal. Katharine Murphy from the Guardian believes that ‘from the moment Biden was projected as the likely winner, Morrison’s language…became noticeably warmer’.

Morrison announced soon after that Australia would not be using the Kyoto carryover credits to meet the 2030 target, but this will not be enough to satisfy the Biden administration.

In an unlikely twist, ex-Prime Ministers Kevin Rudd and Malcom Turnbull teamed up to call on the Morrison government to clamp down on climate policy. Rudd said that in light of Biden’s climate roadmap, Australia should no longer be appeasing ‘Trumpian politics, but instead should be following suit and reducing emissions’.

2030 v 2050 targets —what’s the deal?

One of the more confusing parts of the overall emissions debate is the double-edged sword of having two different targets. So why are there two different targets?

Both targets stem from a framework set by the IPCC in 2018. They warned that in order to avoid global temperatures rising by more than 1.5 degrees, we need to cut global emissions by 45% by 2030, and reach net zero by 2050. This includes all greenhouse (GHG) emissions, not just carbon — meaning big sectors like agriculture and aviation must be included.

These ambiguous targets leave a lot of room for stakeholders to expand their own interests and decrease the rapid transition to a net-zero emissions..

Many businesses are already leading the way towards net zero emissions: BP, Woolworths, Facebook, Australian Super and QBE have all made varying net zero targets in 2020. Meat and Livestock Australia also pledged to be carbon neutral by 2030, citing that by then, Australian beef, lamb and goat production, including feeding and processing, will make no net release of GHG emissions.

Targets are great but what about mechanisms?

It’s great to have a target but without an effective mechanism, targets can remain to be useless.

The Paris Agreement established two market mechanisms and one non-market mechanism to achieve these targets. In plain terms, a market-based approach occurs when a country sets a cap on their GHG emissions, and as a result, the ‘right to emit has the potential to generate a value’. Countries that produce GHG emissions below their target have extra value, meaning they can sell this excess to nations that have not met their targets. Basically, the Paris Agreement created a common currency for trading emissions, creating market-based incentives for nations.

Non-market approaches under the Paris Agreement could include tools that include no transferable units — for example, cooperation on climate policy including jointly developing frameworks like putting a price on carbon or applying taxes to discourage emissions.

Currently, the Australian government utilises the Safeguard Mechanism, which is fulfilled under the Emissions Reduction Fund implemented in 2019. This mechanism requires Australia’s largest GHG emitters to keep their net below an emissions limit. A 2020 study by RepuTex found the mechanism was failing, pointing to a 60% rise in industrial GHG emissions since 2005.

Current Trajectories

At present, Australia needs to step up their game if they want to align with the Paris agreement. A new report released early this year by the Climate Targets Panel found the Morrison government will be effectively abandoning the Paris agreement unless a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions is made by 2030 — and net zero is achieved well before 2050.

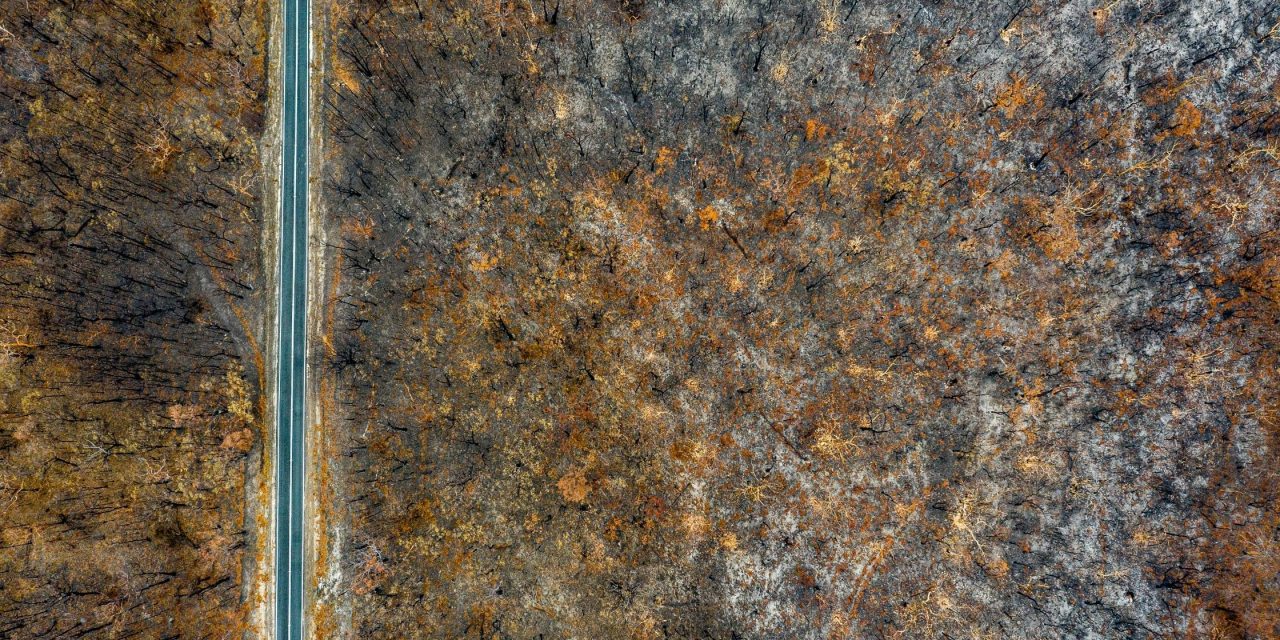

The future of this nation’s climate policy is uncertain at best, but with public debate firing up, talk is cheap for the Australians exposed to the extreme flood and bushfire events of 2020.